We frequently hear from law enforcement leaders that they are struggling to recruit enough quality applicants to fill the law enforcement officer vacancies they currently have or soon will have. Often times, agencies look to university criminal justice programs as a pipeline for future officers. On its face, this strategy is a common sense one. Presumably, one would think that university criminal justice students are highly likely to be interested in police work. One would also imagine that they have some knowledge obtained through their studies that will help them successfully complete the application process and transition into the academy.

In 2018, the School of Criminal Justice at the University of Southern Mississippi published a report entitled, Interest in Police Patrol Careers, that involved a large survey of university students in criminal justice courses. These students were surveyed about their interest in a career in uniformed law enforcement. This interesting study may be of some assistance to law enforcement agencies in determining how to allocate recruiting resources in light of the relevant knowledge and interest traits of the criminal justice students that were surveyed.

The Sample

This study involved a survey of 772 undergraduate students enrolled in criminal justice courses at five large public universities in five states – Illinois State University, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, Missouri State University, University of Massachusetts at Lowell, and University of Southern Mississippi. The overwhelming majority of the respondents were criminal justice students, but their career interests went beyond law enforcement and included the law, private security, corrections, counseling, or forensic science. More than half of the respondents were female (56%), and the racial / ethnic composition of the sample was 72% white, 15% African-American, 7% Hispanic, and 6% all other groups. Two-thirds of the “other” category was composed of respondents who selected “multi-racial” as their race / ethnicity choice. Most of the respondents held positive views of the police within society. Approximately 90% indicated that they had been raised to respect the police, and 88% indicated that the public should respect the police. These undergraduate students were surveyed about their perceptions of employment in law enforcement, the law enforcement officer selection process, and the police academy experience.

It is important to note, however, that many of these students, despite being criminal justice students, lacked a real or accurate understanding of the law enforcement profession. For example, 37% indicated that they did not know what goes on in a police academy, 44% indicated they did not know what a police sergeant does, and 50% indicated they did not know anything about how people were promoted within police departments.

Despite the fact the vast majority were raised to respect the police, and felt the police should be respected, 37% indicated that they believe police officers routinely racially profile citizens, 18% believed police officers shoot citizens frequently, and 25% indicated that they could never in good conscience arrest someone for a marijuana offense.

This discrepancy between the undergraduates’ understanding of police work and reality may be a product of the ideological and theoretical orientation of many state university criminal justice programs today. Less than 10% of full-time criminal justice faculty members at four-year universities today have ever worked as a sworn employee within a law enforcement agency, probation department, or correctional institution, thus having no practical, first-hand knowledge of the criminal justice system to impart. (Note: vocation-oriented community college programs are a clear exception to this trend, with most community college criminal justice faculty members being prior sworn officers.)

Perceptions about the Career

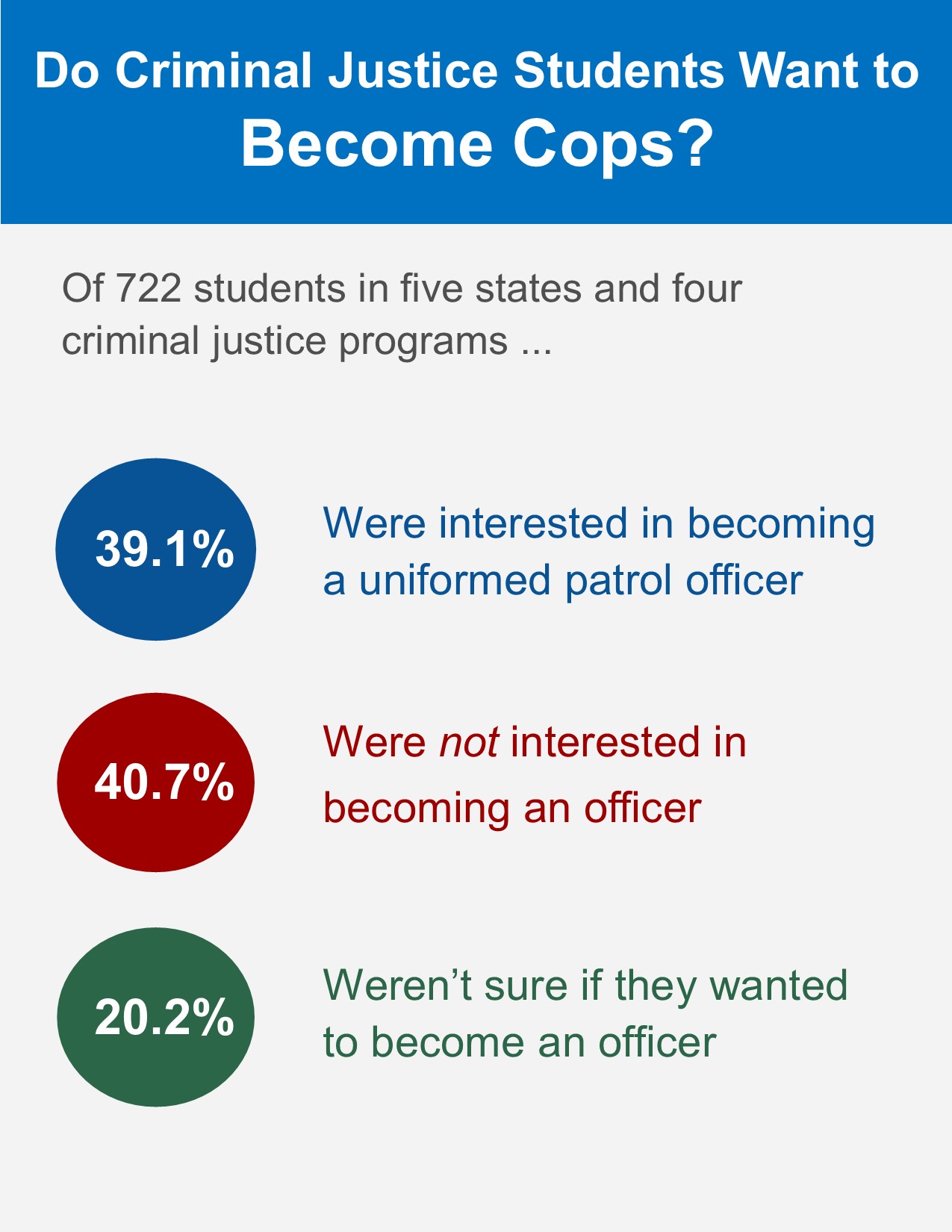

These criminal justice students were asked several questions about their perceptions of law enforcement as a career option. Despite being criminal justice students, or enrolled within criminal justice courses, only 39.1% of students were interested in employment as a uniformed patrol officer, 40.7% were definitely not interested in this work, and 20.2% were not sure. The greatest barriers to pursuing law enforcement as a career option were students’ concerns about compensation and the demands of the job. Approximately 39% of the sample indicated that they thought the salary of a patrol officer would not support the kind of lifestyle they wanted. Keep in mind that these were criminal justice students, so their other career options would be private security, corrections, counseling, forensic lab analyst, defense attorney, or prosecutor—all of which usually have salary ranges similar to, or less than, those of police officers.

Likely these students do not really know how much police officers actually make, or how little these other occupations make. Barring a few isolated exceptions, most law enforcement officers make a middle class wage. Some officers, through overtime pay, earn even more. Agencies may improve their recruiting efforts through communicating how their officers’ salaries, benefits packages, and retirement plans compare to those of other criminal justice careers, or other middle class careers such as teachers, postal workers, nurses, or firefighters.

Almost a quarter of the students (23%) felt that police work was too stressful for them. More than 20% of the students also felt a law enforcement career would interfere with raising a family. The students may have a point here. The evidence does reveal that, compared to other middle class careers, law enforcement officers experience higher rates of divorce and other family dysfunction. This has been attributed to stress, shift work, seeing the worst behavior of humanity, and hypervigilance. Nevertheless, the medical profession, especial nursing and medical technicians (radiology, phlebotomy, etc.) do not have the same high rate of family life dysfunction, despite similar stress, shift work, and constant exposure to death and people in pain. Perhaps the law enforcement profession could benefit from investigating what differences in the work environment of medical workers and law enforcement officers contributes to these differences in family life outcomes.

Only 12% indicated that they were too fearful of the physical force aspects associated with police work. Similarly, only 10% indicated that they were afraid of using firearms. Clearly, concerns about physical dangers were only a barrier for an inconsequential number of criminal justice students.

Only 14% of the students indicated that their families would not approve of their choice if they selected law enforcement as a career. This varied by race as 28% of African-Americans indicated that their family would not approve, compared to 17% for Hispanics, 10% for whites, and 13% for all other groups. One may initially perceive that this is due to racial differences in views about the legitimacy of the police, but a follow-up question revealed that this issue is far more complex. Only 6% indicated that they would be worried about being labelled as racist for becoming a police officer, and there was no difference between whites and African-Americans in response to this question (7% for African-Americans, 2% for Hispanics, 7% for whites, and 4% for all other groups). These results indicate that family disapproval of a law enforcement career for these students is small and has more to do with concerns about danger, salary, and perceptions of social status of the career rather than race and legitimacy issues.

Clearly the greatest barriers to considering law enforcement as a profession were concerns about earnings—concerns that were probably unrealistic—and more valid concerns about stress and family life consequences. This suggests that law enforcement agencies seeking more applicants could benefit from clearly communicating to potential applicants how their pay and benefit packages compare to other middle-class careers and taking all reasonable steps to manage officer stress and improve family quality of life circumstances.

Perceptions about the Selection Process

Only 16% of the students were scared of having their backgrounds exposed through the law enforcement selection process. Related to this finding, 5% believed their prior criminal history would damage their chances of being hired, 8% worried their past social media posts would disqualify them, and 14% believed their past drug use would prevent their hiring.

While the intrusiveness of the background check was not a deterrent to the vast majority of these students, many were intimidated by the physical fitness requirements. A full 27% indicated that they were afraid of the physical fitness test or the physical fitness training standards they would face in the academy. This trepidation was greater among women, as 42% of the female respondents had apprehensions about the physical fitness standards, compared to only 11% of the male respondents. Physical fitness is a real barrier to applicants and this problem is not going away.

According to 2016 statistics from the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics, 36.9% of Americans aged 20 through 25 are obese (body mass index of greater than 30% body fat). This statistic only refers to obesity and does not count the additional people who are simple overweight or out of shape to a degree that would prevent them from meeting the physical fitness standards for entry as law enforcement officers. Furthermore, university criminal justice programs in the nation rarely require any physical education courses.

As a result, law enforcement agencies may benefit from physical fitness related outreach or career preparation programs. As a form of community outreach to middle schools, high schools, and colleges, perhaps law enforcement officers could provide programs that emphasize getting and staying in good health. Law enforcement agencies (or collaborations between multiple public safety agencies) might seek to establish pre-employment indoctrination programs geared to prepare applicants for the physical rigors of the selection process and the academy (not to try to wash applicants out). Perhaps law enforcement agencies can create applicant preparation programs that meet once or twice a week to help potential applicants get into shape, improve test-taking skills, and learn about the department.

Perceptions about the Academy

The vast majority of the surveyed criminal justice students understood the necessity of police academy training. Only 6% saw having to attend a police academy as a “deal breaker,” and 13% indicated that they would be apprehensive about attending an academy. Only 7% perceived police academy training as too long. Nevertheless, more than a fifth of the males, and almost half of the females, indicated that they were intimidated by the physical fitness requirements encountered within the academy. This, again, emphasizes the potential impact of positive, proactive outreach efforts regarding physical fitness might have on recruiting efforts.

Conclusion

The information obtained from this large study of criminal justice students revealed several important facts. First, there appears to be no indication that criminal justice students have significantly more knowledge about the realities regarding the law enforcement profession than do other college students. Their education has emphasized sociological concepts and theories, not the practicalities of police work. To attract these students as applicants, law enforcement agencies need to educate them about the realities of the profession, especially its pay, benefits, roles, and responsibilities. Agencies should exploit every opportunity they have to speak to college classes or student clubs, and offer internships where students get to see the realities of the job, but not limit themselves to just criminal justice students.

Second, law enforcement agencies need to continue emphasizing employee physical and psychological wellness to help current employees cope with the stress and rigors of the job while reducing officer hypervigilance. Agencies should explore what other public services occupations do differently that result in more stable families than does the law enforcement profession.

Third, if law enforcement agencies expect applicants from a predominantly overweight and obese nation to pass their physical fitness requirements, they are going to have to engage in more proactive efforts to help potential applicants prepare for these rigors. Doing so can improve the hiring chances of female applicants, as well as improve public perceptions of the police.

Finally, in light of the study’s findings, law enforcement agencies must resist the temptation to assume that university criminal justice programs are necessarily pre-academy pipelines for employment. Rather than producing young men and women who have a keen understanding of police work, this study suggests that non-practitioner professors are producing students who have a striking lack of knowledge about the profession, and a striking lack of interest in the profession. If this study is indicative of university criminal justice programs nationwide, law enforcement agencies may want to be cautious not to overly invest in university criminal justice students when looking for the next generation of law enforcement officers.