The shortage of qualified applicants for sworn law enforcement positions has become a crucial problem, and shows no signs of improving in the coming years.[i] Due to declining birth rates since the early 1970s, the percentage of the U.S. population that is entering the workforce continues to decline.[ii] Obesity in America is on the rise, as overall physical fitness declines, making it harder to find physically qualified candidates.[iii] Mental health and substance abuse issues have skyrocketed since 2008, making it more difficult to find psychologically qualified candidates.[iv] Our economy currently faces an unprecedented labor market trend in which employees are resigning from their jobs in massive numbers to pursue different careers with higher pay, better working conditions or a better work-family life balance.[v] As a result, law enforcement leaders are being forced to reexamine “the way we’ve always done things” in order to find solutions to this recruiting crisis without lowering standards regarding the character, competence and integrity of potential applicants.

Many law enforcement leaders are reexamining what are truly bona fide minimum requirements for selecting law enforcement officers. While mental and physical fitness and a background that demonstrates high character are undoubtedly necessary requirements for becoming a law enforcement officer, college credit requirements, age limits in the 30s and other long standing automatic disqualifiers are being debated within agencies that are struggling to find qualified applicants. It is becoming increasingly difficult to justify rejecting otherwise qualified applicants, for instance, because they happen to be 40 years old or never attended college, as officer vacancies increase.

The recruiting crisis has reached a level which calls for an open and honest reexamination of minimum qualifications to determine if each one is truly necessary, or simply a best-case-scenario preference. A mandatory requirement that applicants must be U.S. citizens (by birth or naturalization) before being hired as law enforcement officers is one of the qualifiers that law enforcement leaders and elected officials should consider reexamining.

In this article, we will review the historical link between policing and immigration, examine the characteristics of the present immigrant population in the U.S. and then examine the potential barriers to immigrants serving within law enforcement. In this discussion, however, please note that when we refer to immigrants to the U.S., we are referring to those within the borders of the U.S. legally, such as those on student visas or resident aliens (i.e., those with “green cards”), not those within the borders of our nation in direct violation of the laws of the United States. This distinction is extremely important, because we view law-abiding behavior as a non-negotiable minimum standard for working in law enforcement.

Immigrants and Policing

The modern form of policing (i.e., municipal agencies, uniformed patrol, providing around the clock service, etc.) entered American history in the 1830s, especially in the major cities of the Northeast and Midwest. For most of the first century of American law enforcement history, the profession was widely viewed as a low-status job.

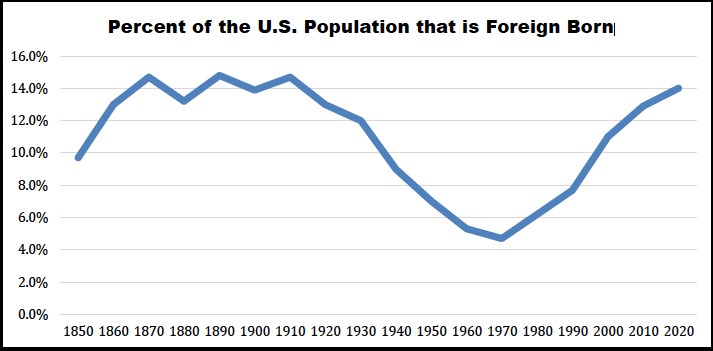

Maintaining the peace in the overpopulated urban squalor of the early industrial revolution, while working alone with only a wooden club and a whistle to call for help, proved an unattractive job when compared to much higher-paying work opportunities in local factories. The job was dangerous and the pay was low. Recruiting was difficult and turnover was high—much as it is today. As a result, the majority of those individuals working as watchmen, constables, and “coppers” in American cities in the 1800s were immigrants – primarily Irish, Italian, German, Polish, Greek and Ashkenazi Jews.[i] This was the case from the period of the U.S. Civil War to World War I. Immigration to the U.S. soared during this era. Table 1 below illustrates the fluctuations in immigration over U.S. history. Immigrant labor was plentiful and cheap from the 1860s through the 1920s, so many immigrants took the jobs in policing that few wanted.

Table 1. U.S. Immigration Trend, 1850-2020

Data Source: U.S. Census Bureau

For these six decades (1860s-1920s), between 13% and 15% of the U.S. population was foreign-born. This era was followed, however, by a huge drop in immigration throughout most of the twentieth century. As a result, many Americans forgot what it was like to live in a society with immigrants occupying many needed positions in American society. Yet, over the last two decades, the percentage of foreign-born persons in the U.S. has returned to nineteenth century levels. Between one and two out of every ten persons in the U.S. today is an immigrant.

Immigrant representation within the law enforcement profession dropped off tremendously throughout most of the twentieth century, primarily because immigration itself had dropped off.[ii] Nevertheless, those who remained working in law enforcement were disproportionately the descendants of the early immigrant police officers. This is why the ethnic backgrounds of officers in the Midwest and Northeast are disproportionately those of the immigrant groups mentioned earlier—Irish, Italian, German, Polish, Greek and Ashkenazi Jews. However, because we have just come out of an 80-year period during which immigration was not nearly as common, the practice of employing immigrants in law enforcement seems rather strange to many in our era.

It should also be noted that the U.S. military has a similar history, while the military never actually dropped its practice of employing immigrants. Throughout its entire existence, from the Revolutionary War to today, there has never been a period when the U.S. military did not have foreign nationals serving within its ranks. Approximately half of the U.S. Army soldiers who served on the Great Plains during the Indian Wars (1866-1891) were immigrants serving in the Army to earn their citizenship.[iii] This practice continues today, as the U.S. military currently accepts non-citizen recruits who may qualify for citizenship, with the expectation that the individual will be granted naturalized citizenship upon earning an honorable discharge.[iv] As of 2013, 5% of new enlistments in the U.S. military were non-citizen individuals.[v] If selected non-citizens can serve under arms in the U.S. military and pass background checks for security clearances, we should consider the possibility that they can carry a weapons as police officers and complete pre-employment background checks.

Current Documented Immigrant Demographics

According to estimates from the Pew Research Center, of the 46 million foreign-born persons presently in the U.S., 45% are naturalized citizens, 27% are permanent resident aliens, and 5% are temporary residents (mostly students). The remaining 23% are unauthorized (illegal) residents. The majority of the current U.S. foreign-born population comes from Latin America (Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba) and Asia (India, China, Philippines, Vietnam, and South Korea).[vi]

Contrary to widely held stereotypes, 73% of the documented immigrant population has the equivalent of a high school education, and 32% hold a college degree. Some even held professional credentials as doctors, lawyers, engineers, nurses or school teachers in their nation of origin.[vii]

The foreign-born population is distributed widely across the nation, but it is most concentrated in the 13 states listed in Table 2 below. These 13 states are also some of the states struggling most with finding qualified applicants to fill law enforcement officer vacancies. It is noteworthy, then, that a number of the states that are as much as 15% to 23% foreign-born, have prohibited non-citizens from consideration for employment in law enforcement. In such states, automatically disqualifying non-citizens instantly eliminates a sizable portion of the potential applicant pool.

A quick scan of Table 2 also reveals that this issue is not solely determined by the state’s political orientation. Conservative states like Texas, and liberal states like California and Hawaii, have opened the profession to qualified non-citizens. Meanwhile, liberal states like Massachusetts, New York, Connecticut and Rhode Island join conservative states like Florida in barring non-citizens from the law enforcement profession. It seems possible, then, that the conversation around non-citizens as sworn officers may be an issue of practicality and logistics more so than liberal versus conservative politics.

Table 2. Foreign-born Concentrations and Employability in Law Enforcement

Data Sources: U.S. Census Bureau and each state’s police standards and training (POST) website.

Potential Barriers to Non-Citizen Officers

There are a number of potential barriers to employing non-citizens as law enforcement officers. First, as revealed in Table 2, are state laws. Obviously, if your state law bars non-citizens from serving as law enforcement officers, your agency cannot hire such individuals. But are these laws well-suited for today’s circumstances? If not, your chiefs’ and sheriffs’ associations are entities that could lobby for a change in the law.

Another barrier is immigrant classification. Under federal law, non-citizens must have permanent resident status, or be students with work visas, before they can be lawfully employed within the United States. This would limit law enforcement agencies to considering only individuals such as these for employment. Luckily, of the non-citizens currently in the country (legally or illegally), more than half (approximately 58%) fit this categorization for lawful employability.

The other minimum employment qualifications may also be a barrier. Can the applicant speak and read English at a proficient level? Does the applicant have the equivalent of at least a high school education? Does the applicant have a valid driver’s license? Does the applicant meet the minimum physical and mental qualifications? Can the applicant complete the physical and academic requirements of the academy? These practical issues seem like potentially insurmountable barriers, until we consider that for the last two decades, the U.S. military has been able to recruit more than 20,000 non-citizens annually who were permanent resident aliens, could pass a written and spoken English proficiency test, pass an intelligence test, pass a military physical and psychological screening and complete the rigors of basic training.[viii] Many of the individuals that successfully met the entry standards for military service may have also met the entry standards for law enforcement employment.

On the surface, it would seem that conducting a background check on a non-citizen would be another barrier. How does a local law enforcement agency check the past of someone who, until recently, lived in another country that speaks another language? Nevertheless, if the applicant has secured permanent resident status, the applicant has already provided the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services with a mountain of documentation which federal investigators have both examined and vetted. Obtaining that permanent resident application packet will provide a vast amount of information on the applicant’s background and associations.[ix] Furthermore, the U.S. military faces the same challenges when screening non-citizen service members for security clearances, yet is still able to successfully conduct these clearance investigations. This does not mean that every non-citizen legally authorized to work in the U.S. will be eligible for a background investigation thorough enough to meet your agency standards. It does mean that the categorical rejection of all non-citizens will likely exclude applicants who could withstand such a background investigation.

Finally, a lack of knowledge among eligible candidates is surely a barrier. Many people do not realize that non-citizens can serve in our military and, similarly, most people likely do not realize that non-citizens could serve as law enforcement officers without some form of proactive outreach effort. This barrier would require intentional recruiting efforts to advertise that non-citizens can also apply and educate qualified candidates on the benefits of a law enforcement career.

Conclusion

In critical professional positions—from priests to nurses to doctors—non-citizens serve an essential role in the everyday lives of Americans. If we entrust legally authorized non-citizens to serve in these roles, is it time to consider similar eligibility for service as sworn law enforcement officers in the face of an unprecedented staffing crisis?

If the U.S. military is able to attract tens of thousands of qualified, non-citizen applicants, the law enforcement profession should consider the possibility of doing so as well. Military service requires risking one’s life, submitting to strict discipline and surrendering a number of basic personal freedoms such as choice of job, place of residence, ability to see one’s family and going home after an 8-hour workday—all for low pay. If tens of thousands of qualified non-citizens are willing to serve in the U.S. military under these conditions, how many more might be willing to serve in a law enforcement career with better pay, set shifts, a choice of where to live and the ability to see their families at the end of the workday?

Recruiting qualified non-citizens is not a quick fix that will solve our law enforcement recruiting crisis, nor is raising the maximum age for applicants, waiving college credit requirements or any other change to “the way we’ve always done things”. But as law enforcement leaders look for the best possible options for staffing their agencies now and in the years ahead, it may be one of many new options that can help us weather the storm that we are facing when it comes to officer staffing.

About the Authors

Matt Dolan, J.D.

Matt Dolan is a licensed attorney who specializes in training and advising public safety agencies in matters of legal liability, risk management and ethical leadership. His training focuses on helping agency leaders create ethically and legally sound policies and procedures as a proactive means of minimizing liability and maximizing agency effectiveness.

A member of a law enforcement family dating back three generations, he serves as both Director and Public Safety Instructor with Dolan Consulting Group.

His training courses include Should Non-Citizens Be Cops? Legal and Practical Considerations, Internal Affairs Investigations: Legal Liability and Best Practices, Supervisor Liability for Law Enforcement, Recruiting and Hiring for Law Enforcement, Confronting the Toxic Officer and Confronting Bias in Law Enforcement.

Richard R. Johnson, Ph.D.

Richard R. Johnson, PhD, is a trainer and researcher with Dolan Consulting Group. He has decades of experience teaching and training on various topics associated with criminal justice, and has conducted research on a variety of topics related to crime and law enforcement. He holds a bachelor’s degree in public administration and criminal justice from the School of Public and Environmental Affairs (SPEA) at Indiana University, with a minor in social psychology. He possesses a master’s degree in criminology from Indiana State University. He earned his doctorate in criminal justice from the School of Criminal Justice at the University of Cincinnati with concentrations in policing and criminal justice administration.

Dr. Johnson has published more than 50 articles on various criminal justice topics in academic research journals, including Justice Quarterly, Crime & Delinquency, Criminal Justice & Behavior, Journal of Criminal Justice, and Police Quarterly. He has also published more than a dozen articles in law enforcement trade journals such as the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, Police Chief, Law & Order, National Sheriff, and Ohio Police Chief. His research has primarily focused on police-citizen interactions, justice system responses to domestic violence, and issues of police administration and management. Dr. Johnson retired as a full professor of criminal justice at the University of Toledo in 2016.

Prior to his academic career, Dr. Johnson served several years working within the criminal justice system. He served as a trooper with the Indiana State Police, working uniformed patrol in Northwest Indiana. He served as a criminal investigator with the Kane County State’s Attorney Office in Illinois, where he investigated domestic violence and child sexual assault cases. He served as an intensive probation officer for felony domestic violence offenders with the Illinois 16th Judicial Circuit. Dr. Johnson is also a proud military veteran having served as a military police officer with the U.S. Air Force and Air National Guard, including active duty service after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Before that, he served as an infantry soldier and field medic in the U.S. Army and Army National Guard.

His training courses include Reporting Accurate Traffic Stop Data: Evidence-Based Best Practices , and Safe Places: Protecting Places of Worship from Violence and Crime.

References

[i] Travis III, Lawrence F., & Langworthy, Robert H. (2007). Policing in America: A Balance of Forces, 4th Edition. New York: Pearson; Wadman, Robert C., & Allison, William T. (2003). To Protect and to Serve: A History of Police in America, 1st Edition. New York: Pearson.

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Utley, Robert M. (1984). Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866-1891. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

[iv] Hattiangadi, Anita, Quester, Aline, Lee, Gary, Lien, Diana, & MacLeod, Ian (2005). Non-Citizens in Today’s Military: Final Report. Arlington, VA: CAN Corporation. Available here: https://www.cna.org/archive/CNA_Files/pdf/d0011092.a2.pdf

[v] Barry, Catherine N. (2013). New Americans in Our Nation’s Military: A Proud Tradition and Hopeful Future. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

[vi] Budiman, Abby (2020). Key Findings about U.S. Immigrants. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

[vii] Budiman, Abby (2020). Key Findings about U.S. Immigrants. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

[viii] Barry, Catherine N. (2013). New Americans in Our Nation’s Military: A Proud Tradition and Hopeful Future. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

[ix] See U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, How to Apply for a Green Card? Accessed at: https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/how-to-apply-for-a-green-card

[i] Dolan, Matt, & Johnson, Richard R. (2022). Weathering the Storm in Police Staffing? Raleigh, NC: Dolan Consulting Group

[ii] Kearney, Melissa, Levine, Phillip, & Pardue, Luke (2022, February 15). “The mystery of the declining U.S. birth rate.” Econofacts. Accessed on 09/26/2022 from: https://econofact.org/the-mystery-of-the-declining-u-s-birth-rate

[iii] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). National Center for Health Statistics Fast Facts: Weight Status and Size. Washington, DC: Center for Disease Control. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/obesity-overweight.htm

[iv] Mental Health America (2021). Mental Health in America, 2020. Alexandria, VA: Mental Health America. Available at: https://mhanational.org/issues/mental-health-america-printed-reports; Hedegaard, Holly, Curtin, Sally, & Warner, Margaret (2020). Increase in Suicide Mortality in the United States, 1999–2018. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db362.htm

[v] Fuller, Joseph & Kerr, William (2022, March 23). “The Great Resignation didn’t start with the pandemic.” Harvard Business Review. Accessed on 09/26/2022 from: https://hbr.org/2022/03/the-great-resignation-didnt-start-with-the-pandemic