Many law enforcement agencies today are struggling to recruit enough quality applicants to fill the officer vacancies they currently have or will have soon. As a result, law enforcement agencies need evidence-based information about how to increase the effectiveness of their recruiting efforts to attract more qualified applicants. Unfortunately, many agency leaders have been forced to rely on anecdotal stories of what drew a particular individual to law enforcement as the basis for formulating recruiting strategies. This approach is far from evidence-based and, instead, relies on the experience of a small group of decision-makers who may, or may not, represent the qualified applicants agencies are seeking. How do we determine that what drew you to law enforcement is what drew others? An extensive nationwide study would be a very good start.

In recent years, several studies have examined the motivations or interests in seeking a law enforcement career among members of the general public, college students, and police academy applicants. Studies of these populations can prove useful, but they also suffer from a notable limitation—not all of the participants may have had the qualifications, skills, and abilities to successfully become law enforcement officers. Furthermore, these studies involved samples of a few hundred participants.

Dolan Consulting Group (DCG) sought to overcome these limitations by conducting a large-scale survey of existing law enforcement officers from across the nation to determine what factors influenced them to pursue a law enforcement career. By focusing on existing law enforcement officers, we explored the experiences of individuals who had the necessary skills and temperaments to successfully gain employment as law enforcement officers. We surveyed 1,673 law enforcement officers from across the nation to determine what factors most influenced them to choose their current profession.

The Sample

Sworn law enforcement officers who attended the various training courses offered by DCG between August 2018 and March 2019 were given the opportunity to participate in our DCG Police Recruiting and Hiring Survey.

A total of 1,673 sworn personnel took the survey, of whom 286 (17.1%) were female and 1,387 (82.9%) were male. The racial composition of the respondents was 83.4% White (non-Hispanic), 6.8% African-American, 5.4% Hispanic, 1.4% Multiracial, 1.0% Native American, 0.4% Asian, and 1.6% all other groups. In terms of highest education level achieved, 30.8% had less than an associate’s degree, 18.2% had an associate’s degree, and 51% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. A total of 52.8% of the respondents held the rank of officer, deputy, or trooper, while another 10.0% held the rank of detective. About 23% held first-line supervisory ranks (corporal or sergeant), 4.5% held middle-management ranks (mostly lieutenants), and the remaining 9.7% held command staff ranks (captain or higher). Approximately 65% of the respondents were assigned to the patrol division of their agency, 14% to investigations, and 14% to command administration. The remaining 7% indicated other assignments such as training, community policing unit, or media relations. These respondents came from 49 different states and agencies ranging in size from less than a dozen officers to agencies with thousands of officers.

Reasons for Selecting a Law Enforcement Career

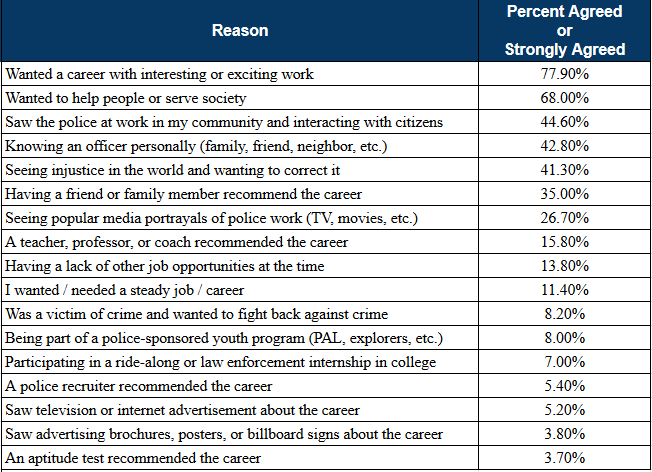

The survey respondents were presented with a list of 17 factors that might have influenced them to pursue a career in law enforcement. The respondents were asked to reflect on their own lives and indicate if each of these factors played a role in shaping their decision to become a law enforcement officer. For each of these 17 factors, the respondents indicated their level of agreement (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) regarding the extent to which each factor influenced their career choice. The survey results are displayed in Table 1 on the next page, showing the percentage of respondents who answered agree or strongly agree with each statement.

The results in Table 1 reveal several common themes. First, a sizeable proportion of the sample chose a career in law enforcement because of the excitement associated with the career as almost 78% wanted a career with interesting or exciting work, 45% watched the police at work in their communities, about 27% were drawn by popular entertainment media portrayals of the career, and 7% selected the career after seeing it first-hand through a ride-along or college internship. Second, a great proportion of the respondents wanted to help people in society (68%), wanted to address injustice in society (41%), or wanted to fight back after having been a victim of crime (8%).

The third theme that was evident in the responses was the importance of personal relationships in one’s life on deciding to pursue a law enforcement career. Approximately 45% were influenced to pursue a law enforcement career by personally interacting with officers who were at work in the community, 43% were influenced by knowing an officer personally (family member, friend, neighbor, etc.), 35% had a friend or family member recommend the career, 16% had a teacher, professor, or coach recommend the career, and 8% had interacted with officers in a police-sponsored youth program (camp, police athletic league, explorers program, etc.).

Table 1. Reasons for Selecting a Law Enforcement Career

The final trend evident in the results was the relative insignificance of formal recruiting activities in effecting the respondents’ decisions to pursue a law enforcement career generally. (Please note that this does not indicate that formal recruiting and advertising were necessarily ineffective in attracting a particular individual to a particular department within the law enforcement profession). Less than 6% of the respondents credited a recruiter or formal advertising of any kind as having influenced their decision to become a law enforcement officer. In fact, a simple lack of other job opportunities (14%) was more than twice as strong an influence as were formal recruiting activities.

Conclusions

These results suggest that most individuals who are drawn to law enforcement are drawn as a uniquely exciting and honorable profession in which they can help people. In spite of high profile instances of officer misconduct accompanied by overwhelming media coverage, the law enforcement profession remains one of the most highly respected institutions in American life (See the DCG research brief The Public’s Confidence in the Police Might Be Higher Than You Think). Anything that a member of law enforcement can do to maintain the public trust is, in and of itself, a recruiting strategy.

The most effective police recruiting efforts appear to involve all members of the department developing personal relationships with people in the community on and off the clock (family members, neighbors, students, and average people on the patrol beat). People on the department need to talk to members of their community about how noble, rewarding, and exciting a law enforcement career is. When officers personally advertise the nobility of their profession, in both word and deed, people who desire an exciting career that involves helping people and fighting injustice are drawn to the profession.

The most important steps any law enforcement agency can take in order to improve recruiting efforts include:

Protect the public’s trust in the police. In whatever capacity you find yourself within an organization, do what you can to minimize the misconduct, unnecessarily hostile community interactions, and viral videos that steer people away from law enforcement those individuals drawn to an exciting career in which they can help people. These same efforts serve to maintain the help of the many advocates in communities across the country—parents, family, friends, coaches and teachers—who encourage those they mentor to join law enforcement.

With this broad view, it becomes clear that anything that weakens the relationship between the police and the public hurts recruiting. Poor supervision hurts recruiting. Failure to mentor young officers who are struggling hurts recruiting. Failures by command staff to heed the warnings of front-line supervisors before poor performance escalates to newsworthy police misconduct that hurts recruiting.

Seriously embrace the idea that every member of your department is a recruiter—for better or worse. Empower and encourage all personnel to engage in recruiting efforts, both on and off duty. Empress upon your personnel that the qualities of the individuals they attract to the department will determine their type of future coworkers and work environment. Encourage them to seek out people in the community with qualities and skills they would like to see in their coworkers, and recruit these people.

Unimpressed with the number or quality of applicants? Concerned about the prospect of working with the applicants walking through the door? Then do something about it. Utilizing citizen interactions as an opportunity to vent frustrations about the profession doesn’t help. Take the same steps that we ask of community leaders critical of recruiting efforts—become part of the solution and personally invite men and women of character to the profession.

Create opportunities to connect with potential applicants and potential advocates. Create as many opportunities for personnel on your department to develop personal connections with individuals who might someday become law enforcement officers, as well as the parents and mentors who might someday recommend the career to others. During unassigned time on duty, encourage officers to be out of their cars, and supervisors away from their desks, in order to get to know average citizens. Get law enforcement officers into the schools as much as possible for the purposes of fostering positive interactions between youths and officers. Sponsor youth sports, explorer, and internship programs to further foster these contacts. Develop a citizen police academy and promote a ride-along program for qualified individuals, to expose average citizens to the realities of the career and the people on the department. Lastly, invite people to participate in the ride-along or citizen police academy programs.

Make personal invitations. Policing tends to be an insular career that often makes non-law enforcement officers feel like outsiders. Many law enforcement officers are also family members, thus further strengthening the impression to outsiders that the career in an exclusive club. Many of the respondents in our survey, however, indicated that someone in their lives had personally recommended the career to them as individuals. This reveals the power of the personal invitation. When a member of your department finds a good potential applicant, it may not be enough just to share information about the department or the career. Personnel should personally invite the person to complete the application process or do a ride-along, also telling the individual specifically why he or she might make a good police officer.

Tone down the negativity. Because law enforcement officers often see the worst of society, it is easy to become negative, jaded, and cynical. However, few people want to join a profession or organization that seems full of negativity. What is particularly damaging is when law enforcement officers argue—privately and in sometimes in public—that they would discourage their own children from becoming officers. If we would not want our sons and daughters to become officers, how can we expect other people’s sons and daughters to join our ranks?

Lastly, media interviews should not be viewed as an opportunity to publicly vent about the downsides of a law enforcement career and explain why you’re not surprised that people aren’t applying. If we want to attract quality applicants, and draw more good people to this career field, then we need to speak positively about the profession when interacting with the public.

For a more in-depth discussion of ways to improve your agency’s recruiting efforts, you can learn more about our Recruiting and Hiring for Law Enforcement classes at the link below: